By Ken Robison

[Published in the Fort Benton River Press 16 May 2007]

This continues the series of historical sketches by historians at the Joel F. Overholser Historical Research Center in Fort Benton.

Tillie Wallace was no angel. She got caught—the only lady known to be prosecuted for running her own moonshine operation in Montana during Prohibition from 1919 to 1933. But Tillie was more than a moonshiner. She was also a mother, a widow, a homesteader and rancher located northwest of the bustling cow and railroad town of Square Butte in southern Chouteau County.

“Tillie” or Mathilda J. Wallace was born in Minnesota in 1879, married at age 17, and in 1910 lived in Minnesota with her husband Joseph and 8-year-old daughter Carmilla. By 1912 Tillie was a widow, and she and Carmilla headed west on the Great Northern Railroad to homestead in southern Chouteau County.

In the early years all went well for homesteader Tillie, and in 1919 she proved up her claim to receive patent to 317.45 acres. Over the years, Tillie acquired more land and her place became known as the Tillie Wallace Ranch, but then the hard times of the 1920s struck. A friend of hers that she owed money to agreed to furnish her with a still and let her pay off what she owed him by making moonshine whiskey. Tillie agreed to the deal in hopes of paying off the mortgage and saving her farm. She set up the still in a crude granite stone shack with a metal roof hidden among the large granite boulders some 75 feet above her ranch buildings. The shack’s location gave a clear view of The Sag, both east and west, with a towering cliff wall in back.

Tillie was in the moonshining business for several years before

Federal agents J. Q. Adams and Richard Ginn [what a great name for a revenuer] raided the ranch late Saturday afternoon January 2, 1932. The agents searched the ranch, seized a completely outfitted 75-gallon still operation in the stone shack, and destroyed six 50-gallon barrels and three 10-gallon kegs. She admitted to the officers that she had been in business for some time and that she had ‘run off’ the last batch about two weeks ago.

In April 1932, Mrs. Mathilda Wallace went before Judge Charles N. Pray in District Court in Great Falls on a charge of “possessing machinery to manufacture liquor.” She pleaded guilty, insisted that she has never sold any whisky except to two people, and emphasized that she did not drink herself. Her lawyer related her sad tale of financial troubles and her efforts to save the farm. The agents testified that they found cobwebs over the barrels and that the still hadn’t been used for a long time. Legendary Judge Pray fined Tillie $50 and then empathetically suspended the fine after placing her on probation for three years.

Around the time of the raid on the Tillie Wallace Ranch, the same federal agents also successfully raided the Smoke House pool hall and “soft drink” joint in the town of Square Butte. The agents arrested 81-year-old William Fitzmaurice for violating the national prohibition law by “possessing liquor and maintaining a nuisance.” They seized one-third of a gallon of moonshine whisky hidden in an ice cream container in the back room.

The same day in April 1932 that Tillie went to trial before Judge Pray so did old William Fitzmaurice. His attorney made a strong plea for leniency, and Fitzmaurice pleaded guilty. As the story unfolded, the unidentified owner of the pool hall had left town to go down to Canastota for his health, so he hired Mr. Fitzmaurice to run the place while he was gone. Fitzmaurice had lived in Cascade County for thirty years, and his lawyer told the Judge that his client didn’t know the whisky was there until the officers raided the place.

Judge Pray looked at the old man, whose eyes were clear in spite of his years. The prohibition agent confirmed the statement of Mr. Holt and said he had never heard of anything against Fitzmaurice. When they went there, they were after the proprietor, and they were still looking for him. Judge Pray fined Fitzmaurice $50 on his plea of guilty and then suspended the fine on three years’ probation.

By 1932 the great social experiment of prohibition had failed, and the country waited anxiously for repeal. The federal agents brought the moonshiners and bootleggers in, and the courts, in many cases like those of the two Square Butte operations, let them go. In Tillie Wallace’s case, she was unable to keep the ranch going without the moonshine income and in 1935 she sold out for $10.

p. s. Tillie Wallace may also have been a murderer. We are tracking down rumors and will tell you more about this later.

[Sources: Set in Stone The Square Butte Granite Quarry by Henry L. Armstrong and Marcella Knedler; GFLD 4 Jan 1932, p. 8; GFLD 27 Apr 1932, p. 8; US Census 1900-1930]

Photos:

(1) Tillie Wallace Still Site [Photo by Henry L. Armstrong]

(2) Typical Still and Moonshine Equipment [Great Falls Tribune Photo]

(3) “First Woman ‘Moonshiner’ Is Arrested” [Great Falls Leader Photo]

10 September 2007

Cowboy Up! The Master Saddlers of Fort Benton

By Ken Robison

[Published in the Fort Benton River Press 31 January 2007

This continues the series of frontier sketches by historians at the Joel F. Overholser Historical Research Center in Fort Benton.

If early Montanans rode “tall in the saddle,” that in measure was due to the work of the master saddlers of Fort Benton. During the 1870s ranching began to develop in historic Choteau County, and by the early 1880s open range ranches extended in every direction from Fort Benton. Ranches meant horses, and horses meant an increasing demand for saddles, bridles, harnesses, and other equestrian equipment.

The large mercantile houses in Fort Benton like T. C. Power & Brother offered saddles and other supplies to ranch customers in Montana and southern Canada, but it was only a question of time, before saddle makers would open for business in Fort Benton.

We may never be certain when the first saddle and harness maker opened shop in Fort Benton to fill the rising need, but we do know that L. H. Rosencrans moved from Helena to Fort Benton to become the first known saddle maker in 1876. L. H. Rosencrans, saddler, was open for business by February 2, 1877. His wood frame shop, built by Gus Senieur, was located next to the Benton Record office on the corner of Front and Bond (today’s 14th) streets. Rosencrans’ first ad carried in the February 16th Benton Record stated he was prepared to take orders for any style of harness, saddle, bridle, halter, collar, belt, or whip and that he was prepared to make old harness or saddles “good as new.” His shop over time became known as the Pioneer Harness Shop.

The 1860 Wisconsin census gives insight into Rosencrans’ origins. In that year John and Mary Rosencrans lived in Beloit, Rock County, Wisconsin with a large family including twin boys, Lucius and Lucian, born in April 1847, and a son Milo, born in 1851. Lucian H. Rosencrans arrived in Helena in 1866, one of the first saddlers in Montana Territory, and he remained in Helena for the next decade before moving on to Fort Benton. In June 1880, Lucius, sometimes Lucas, or most often simply “L. H.” Rosencrans lived in Fort Benton and was employed in the saddle and hardware business. In the census of 1880, his twin brother Lucian lived in Helena, and their younger brother Milo was a stock raiser operating out of Fort Benton.

L. H. Rosencrans worked in Fort Benton until June 1883 when he sold his business to William Glassman. He married Marcella that same year 1883, and they remained in Montana until about 1890. The Rosencrans then moved on to Freeborn County, Minnesota with L. H. still working as a harness maker.

William Glassman sold his Cheyenne Saddle Shop in Helena in early 1883, moved to Fort Benton, and on the 13th of June of that year bought the Rosencrans saddlery. William Glassman was born in Davenport, Scott County, Iowa in November 1858 of parents born in Germany. He came west by way of the cattle country of Colorado and Wyoming, and in 1878 was in Miles City. In Fort Benton, Glassman operated his saddle and harness shop at Front and Bond streets. In October 1885, he departed Fort Benton, eventually moving on to Utah. There he went into the real estate business and became active in Republican Party politics. In 1900 Glassman worked as a journalist and lived in Ogden, Utah with his wife Evelyn and two children. William and Evelyn Glassman were married about 1883, and their oldest child, Ethel, was born July 1884 in Fort Benton. Their son, Roscoe, was born in Utah in May 1891. Glassman became a leader of his party in Utah, was elected speaker of the lower house of the Utah legislature, and served as mayor of Ogden.

August Beckman, Fort Benton’s second saddle and harness maker, arrived May 17, 1878 from St. Louis with his family as deck passengers on the steamboat Red Cloud. Beckman had graduated from one of the largest saddle and harness firms in St. Louis. By late May of 1878 his stock of goods had arrived, and Beckman opened the New Harness Shop on Front Street. In June 1880 Beckman, born about 1840 in Germany, worked as a harness maker and lived in Fort Benton with his wife Louisa, also German born, and their four children, all born in Missouri.

In late 1880 Beckman built a two-story 35x40 brick building for his saddlery on Franklin Street between Baker (16th) and Power (17th) streets. His wife Louisa ran a boarding house, the Cosmopolitan Hotel, and restaurant on the upper floor. August Beckman sold his business to S. J. Kline on May 30, 1888, and went into ranching on the Teton River in the 1890s. Both August and Louisa passed away in the 1890s.

The Davidson & Moffitt harness store operated in Fort Benton from 1881 to 1883. This Fort Benton store, managed by John Moffitt, was a branch of the Helena business of A. J. Davidson. The January 1881 Holiday Edition of the River Press, reported that Davidson & Moffitt had recently completed a one-story brick building during 1881 and would add a twenty feet addition in the spring of 1882. Their store was located next to Murphy, Neel & Company, at Front and Arnoux (12th) streets. Davidson & Moffitt were agents at Fort Benton for the celebrated Concord harness and kept in stock “everything required by a horseman.” Besides their saddle and harness business, they dealt in wool, hides, and robes. The store closed in September 1883, and the River Press later purchased the building.

The longest in business and best known of Fort Benton saddlers was Joseph Sullivan. Sullivan with partner V. K. Goss moved to Fort Benton from Deer Lodge at the urging of Johnny Healy. The 1881 Holiday Edition of the River Press reported that this new firm had just commenced business in September in a building formerly occupied by J. J. Kennedy meat market. By July 1882 Goss ended the partnership and returned to Deer Lodge. The well-known sign, “Jos. Sullivan, Saddler’, hung for years over the door of the 1865 building that had housed the Blackfeet Agency and treaty of that year, located on Front Street next door to the Benton State Bank on St. John (15th). The front face of this historic building was log; an addition of adobe was added, and later a third frame structure was added to the rear.

Joseph Sullivan made friends with the cattlemen of the open range, and Charles M. Russell was a special friend. Sullivan died in Fort Benton in April 1940 after 59 years in the business, operating his renowned shop a bit until just before his death. The old building he occupied the entire time was saved and moved to Great Falls by Charles Bovey as an important part of Frontier Town at the Fair Grounds. Jos. Sullivan’s Saddlery was later moved on to Nevada City where it stands today.

Vanderlyn K. or V. K. Goss was born about 1854 in Michigan. In June 1880 he lived in Helena, working as a harness maker, before he moved on to Deer Lodge to form a partnership with Joe Sullivan. After his short time in Fort Benton, Goss married Miss Lou Watson of Mason City, Iowa in early July 1882 in Fort Benton and returned to Deer Lodge to resume business.

Joseph Sullivan was born in Ireland in December 1857 and came to the United States in 1860 as a child. Some sources claim that Sullivan was born at Port Chester, New York about 1860. Young Sullivan visited a brother in St. Paul in 1880 and kept going west to Montana Territory, arriving late that year. For a time he worked in a harness shop in Bozeman, before joining with V. K. Goss to operate a saddlery in Deer Lodge. Joe Sullivan married Rosa V. McQuillan, an early Fort Benton teacher, in 1885 in Dubuque, Iowa, and they had two daughters, Marie B. and Mary G.

Shortly after coming to Fort Benton, Sullivan received an order for 500 lightweight saddles for the North West Mounted Police, so he hired five or six more workers to help meet that order. At that time he had about a dozen employees. Sullivan made saddles for the big T. C. Power concern. Sullivan once said that two cinch saddles were most popular when he first came to Montana, but the mode changed to the three-quarter rig, one cinch. In the words of Joel Overholser, “Sullivan saddles went as far north as Edmonton and south to the Colorado line, and every puncher on the northern ranges knew or knew of Joe Sullivan . . . Joe Sullivan was a crusty old timer; a friend recalled that cowboys would hock their outfits to him to prolong a spree, get a tongue lashing later and be sent back to work with saddle and gear—they usually paid up next time.”

In a tribute to Sullivan in 1940, Overholser wrote, “The death of Joseph Sullivan, pioneer Fort Benton saddler and harness maker, marks the severing of another of Montana’s links to her colorful and picturesque past . . . The men who built the saddles which were cinched onto the hurricane decks of Montana broncs never received any part of the credit going to the cowpuncher who had made a good ride, but they deserved some of it, for when they built their saddles, they built them to last. Joe Sullivan was one of the last of these old-time saddlers.”

A one-time employee of Sullivan’s, Arnold Westfall, operated his own shop on Front Street between St. John (15th) and Baker (16th) streets for a quarter century, from about 1904 to 1931. He made some of the saddles sold by T. C. Power. Westfall was born in August 1862 in Iowa, came to Fort Benton in 1891, and married Hannah E. Johnson in 1893. Hannah was born in Norway and immigrated to the United States in 1881. Arnold and Hannah Westfall had a daughter, Ethel L., born October 1893 and a son, Arnold J., born in February 1898. In 1931 Westfall suffered a stroke and had to close his business. He passed away April 23, 1933.

Little is known of Sam J. Kline (or Cline) who came to Fort Benton in June 1882 to work for Sullivan & Goss. At some point in the 1880s, Kline opened his own harness business on Franklin Street. In May 1888 Kline moved his shop from Franklin to Front Street. Other saddle and harness makers also may have opened their own businesses in Fort Benton over the years after working for Sullivan or other saddlers.

Through the decades, the saddles of Fort Benton’s talented artisans have retained their interest and prestige with ranchers and collectors. Modern day master saddle maker, Dr. Richard Sherer of Denver, triggered this article after he restored a saddle by William Glassman and saddlebags by Joe Sullivan and asked for biographic information. Closer to home, you can see seven Sullivan saddles, some dating from the 1890s, and three Westfall saddles in our remarkable display of historic saddles at the Museum of the Upper Missouri. They are a fitting tribute to the great saddle makers of an important era in Fort Benton’s history.

[Sources: Benton Record (BR) 5 Jan 1877; BR 2 Feb 1877; BR 16 Feb 1877; BR 2 Jun 1878; River Press (FBRP) Holiday Edition 28 Dec 1881; FBRP 16 Jun 1883; FBRP 1 Jan 1884; FBRP 12 Aug 1885; FBRP 21 Oct 1885; FBRP 23 Jan 1901; FBRP 21 Jan 1942; FBRP 5 Aug 1970; FBRP 14 Aug 1974; Sun River Sun 14 Feb 1884; various U.S. Census; Fort Benton World’s Innermost Port by Joel Overholser]

Photographs:

(1) Fort Benton’s first saddler, L. H. Rosencrans, advertised in the Benton Record

(2) Testimony for William Glassman saddles by cowmen in the Judith Basin in the Sun River Sun

(3) August Beckman’s “New Harness Shop” Ad in the Benton Record

(4) An Ad for Davidson & Moffitt from an 1881 River Press

(5) An Ad for Sullivan & Goss from an 1881 River Press

(6) Joe Sullivan standing on the left in front of his famed “Jos. Sullivan Saddler” store on Front Street in Fort Benton with friends artist Ed Borein, rancher Julius Bechard, and an unidentified man

(7) Arnold Westfall, Fort Benton saddler

[Published in the Fort Benton River Press 31 January 2007

This continues the series of frontier sketches by historians at the Joel F. Overholser Historical Research Center in Fort Benton.

If early Montanans rode “tall in the saddle,” that in measure was due to the work of the master saddlers of Fort Benton. During the 1870s ranching began to develop in historic Choteau County, and by the early 1880s open range ranches extended in every direction from Fort Benton. Ranches meant horses, and horses meant an increasing demand for saddles, bridles, harnesses, and other equestrian equipment.

The large mercantile houses in Fort Benton like T. C. Power & Brother offered saddles and other supplies to ranch customers in Montana and southern Canada, but it was only a question of time, before saddle makers would open for business in Fort Benton.

We may never be certain when the first saddle and harness maker opened shop in Fort Benton to fill the rising need, but we do know that L. H. Rosencrans moved from Helena to Fort Benton to become the first known saddle maker in 1876. L. H. Rosencrans, saddler, was open for business by February 2, 1877. His wood frame shop, built by Gus Senieur, was located next to the Benton Record office on the corner of Front and Bond (today’s 14th) streets. Rosencrans’ first ad carried in the February 16th Benton Record stated he was prepared to take orders for any style of harness, saddle, bridle, halter, collar, belt, or whip and that he was prepared to make old harness or saddles “good as new.” His shop over time became known as the Pioneer Harness Shop.

The 1860 Wisconsin census gives insight into Rosencrans’ origins. In that year John and Mary Rosencrans lived in Beloit, Rock County, Wisconsin with a large family including twin boys, Lucius and Lucian, born in April 1847, and a son Milo, born in 1851. Lucian H. Rosencrans arrived in Helena in 1866, one of the first saddlers in Montana Territory, and he remained in Helena for the next decade before moving on to Fort Benton. In June 1880, Lucius, sometimes Lucas, or most often simply “L. H.” Rosencrans lived in Fort Benton and was employed in the saddle and hardware business. In the census of 1880, his twin brother Lucian lived in Helena, and their younger brother Milo was a stock raiser operating out of Fort Benton.

L. H. Rosencrans worked in Fort Benton until June 1883 when he sold his business to William Glassman. He married Marcella that same year 1883, and they remained in Montana until about 1890. The Rosencrans then moved on to Freeborn County, Minnesota with L. H. still working as a harness maker.

William Glassman sold his Cheyenne Saddle Shop in Helena in early 1883, moved to Fort Benton, and on the 13th of June of that year bought the Rosencrans saddlery. William Glassman was born in Davenport, Scott County, Iowa in November 1858 of parents born in Germany. He came west by way of the cattle country of Colorado and Wyoming, and in 1878 was in Miles City. In Fort Benton, Glassman operated his saddle and harness shop at Front and Bond streets. In October 1885, he departed Fort Benton, eventually moving on to Utah. There he went into the real estate business and became active in Republican Party politics. In 1900 Glassman worked as a journalist and lived in Ogden, Utah with his wife Evelyn and two children. William and Evelyn Glassman were married about 1883, and their oldest child, Ethel, was born July 1884 in Fort Benton. Their son, Roscoe, was born in Utah in May 1891. Glassman became a leader of his party in Utah, was elected speaker of the lower house of the Utah legislature, and served as mayor of Ogden.

August Beckman, Fort Benton’s second saddle and harness maker, arrived May 17, 1878 from St. Louis with his family as deck passengers on the steamboat Red Cloud. Beckman had graduated from one of the largest saddle and harness firms in St. Louis. By late May of 1878 his stock of goods had arrived, and Beckman opened the New Harness Shop on Front Street. In June 1880 Beckman, born about 1840 in Germany, worked as a harness maker and lived in Fort Benton with his wife Louisa, also German born, and their four children, all born in Missouri.

In late 1880 Beckman built a two-story 35x40 brick building for his saddlery on Franklin Street between Baker (16th) and Power (17th) streets. His wife Louisa ran a boarding house, the Cosmopolitan Hotel, and restaurant on the upper floor. August Beckman sold his business to S. J. Kline on May 30, 1888, and went into ranching on the Teton River in the 1890s. Both August and Louisa passed away in the 1890s.

The Davidson & Moffitt harness store operated in Fort Benton from 1881 to 1883. This Fort Benton store, managed by John Moffitt, was a branch of the Helena business of A. J. Davidson. The January 1881 Holiday Edition of the River Press, reported that Davidson & Moffitt had recently completed a one-story brick building during 1881 and would add a twenty feet addition in the spring of 1882. Their store was located next to Murphy, Neel & Company, at Front and Arnoux (12th) streets. Davidson & Moffitt were agents at Fort Benton for the celebrated Concord harness and kept in stock “everything required by a horseman.” Besides their saddle and harness business, they dealt in wool, hides, and robes. The store closed in September 1883, and the River Press later purchased the building.

The longest in business and best known of Fort Benton saddlers was Joseph Sullivan. Sullivan with partner V. K. Goss moved to Fort Benton from Deer Lodge at the urging of Johnny Healy. The 1881 Holiday Edition of the River Press reported that this new firm had just commenced business in September in a building formerly occupied by J. J. Kennedy meat market. By July 1882 Goss ended the partnership and returned to Deer Lodge. The well-known sign, “Jos. Sullivan, Saddler’, hung for years over the door of the 1865 building that had housed the Blackfeet Agency and treaty of that year, located on Front Street next door to the Benton State Bank on St. John (15th). The front face of this historic building was log; an addition of adobe was added, and later a third frame structure was added to the rear.

Joseph Sullivan made friends with the cattlemen of the open range, and Charles M. Russell was a special friend. Sullivan died in Fort Benton in April 1940 after 59 years in the business, operating his renowned shop a bit until just before his death. The old building he occupied the entire time was saved and moved to Great Falls by Charles Bovey as an important part of Frontier Town at the Fair Grounds. Jos. Sullivan’s Saddlery was later moved on to Nevada City where it stands today.

Vanderlyn K. or V. K. Goss was born about 1854 in Michigan. In June 1880 he lived in Helena, working as a harness maker, before he moved on to Deer Lodge to form a partnership with Joe Sullivan. After his short time in Fort Benton, Goss married Miss Lou Watson of Mason City, Iowa in early July 1882 in Fort Benton and returned to Deer Lodge to resume business.

Joseph Sullivan was born in Ireland in December 1857 and came to the United States in 1860 as a child. Some sources claim that Sullivan was born at Port Chester, New York about 1860. Young Sullivan visited a brother in St. Paul in 1880 and kept going west to Montana Territory, arriving late that year. For a time he worked in a harness shop in Bozeman, before joining with V. K. Goss to operate a saddlery in Deer Lodge. Joe Sullivan married Rosa V. McQuillan, an early Fort Benton teacher, in 1885 in Dubuque, Iowa, and they had two daughters, Marie B. and Mary G.

Shortly after coming to Fort Benton, Sullivan received an order for 500 lightweight saddles for the North West Mounted Police, so he hired five or six more workers to help meet that order. At that time he had about a dozen employees. Sullivan made saddles for the big T. C. Power concern. Sullivan once said that two cinch saddles were most popular when he first came to Montana, but the mode changed to the three-quarter rig, one cinch. In the words of Joel Overholser, “Sullivan saddles went as far north as Edmonton and south to the Colorado line, and every puncher on the northern ranges knew or knew of Joe Sullivan . . . Joe Sullivan was a crusty old timer; a friend recalled that cowboys would hock their outfits to him to prolong a spree, get a tongue lashing later and be sent back to work with saddle and gear—they usually paid up next time.”

In a tribute to Sullivan in 1940, Overholser wrote, “The death of Joseph Sullivan, pioneer Fort Benton saddler and harness maker, marks the severing of another of Montana’s links to her colorful and picturesque past . . . The men who built the saddles which were cinched onto the hurricane decks of Montana broncs never received any part of the credit going to the cowpuncher who had made a good ride, but they deserved some of it, for when they built their saddles, they built them to last. Joe Sullivan was one of the last of these old-time saddlers.”

A one-time employee of Sullivan’s, Arnold Westfall, operated his own shop on Front Street between St. John (15th) and Baker (16th) streets for a quarter century, from about 1904 to 1931. He made some of the saddles sold by T. C. Power. Westfall was born in August 1862 in Iowa, came to Fort Benton in 1891, and married Hannah E. Johnson in 1893. Hannah was born in Norway and immigrated to the United States in 1881. Arnold and Hannah Westfall had a daughter, Ethel L., born October 1893 and a son, Arnold J., born in February 1898. In 1931 Westfall suffered a stroke and had to close his business. He passed away April 23, 1933.

Little is known of Sam J. Kline (or Cline) who came to Fort Benton in June 1882 to work for Sullivan & Goss. At some point in the 1880s, Kline opened his own harness business on Franklin Street. In May 1888 Kline moved his shop from Franklin to Front Street. Other saddle and harness makers also may have opened their own businesses in Fort Benton over the years after working for Sullivan or other saddlers.

Through the decades, the saddles of Fort Benton’s talented artisans have retained their interest and prestige with ranchers and collectors. Modern day master saddle maker, Dr. Richard Sherer of Denver, triggered this article after he restored a saddle by William Glassman and saddlebags by Joe Sullivan and asked for biographic information. Closer to home, you can see seven Sullivan saddles, some dating from the 1890s, and three Westfall saddles in our remarkable display of historic saddles at the Museum of the Upper Missouri. They are a fitting tribute to the great saddle makers of an important era in Fort Benton’s history.

[Sources: Benton Record (BR) 5 Jan 1877; BR 2 Feb 1877; BR 16 Feb 1877; BR 2 Jun 1878; River Press (FBRP) Holiday Edition 28 Dec 1881; FBRP 16 Jun 1883; FBRP 1 Jan 1884; FBRP 12 Aug 1885; FBRP 21 Oct 1885; FBRP 23 Jan 1901; FBRP 21 Jan 1942; FBRP 5 Aug 1970; FBRP 14 Aug 1974; Sun River Sun 14 Feb 1884; various U.S. Census; Fort Benton World’s Innermost Port by Joel Overholser]

Photographs:

(1) Fort Benton’s first saddler, L. H. Rosencrans, advertised in the Benton Record

(2) Testimony for William Glassman saddles by cowmen in the Judith Basin in the Sun River Sun

(3) August Beckman’s “New Harness Shop” Ad in the Benton Record

(4) An Ad for Davidson & Moffitt from an 1881 River Press

(5) An Ad for Sullivan & Goss from an 1881 River Press

(6) Joe Sullivan standing on the left in front of his famed “Jos. Sullivan Saddler” store on Front Street in Fort Benton with friends artist Ed Borein, rancher Julius Bechard, and an unidentified man

(7) Arnold Westfall, Fort Benton saddler

Hope & Opportunity: Homesteading in Montana 1909-1920

By Ken Robison

[Published in the Fort Benton River Press 11 July 2007. The article accompanied a Homestead Photography Exhibition at the entrance to the Museum of the Northern Great Plains during summer of 2007. This Exhibition will be in the Great Falls Public Library during May-June 2008.]

This continues the series of sketches by historians at the Joel F. Overholser Historical Research Center in Fort Benton.

The men and women who came to claim free land in Montana through homesteading faced many trials and tribulations as they worked through the good and bad times. Visual insight into the experiences of these hearty men, women, and children will be on display throughout this summer at the entrance to our Museum of the Northern Plains. The exhibition is built from the broad collection of imagery and memorabilia held at the Overholser Historical Research Center and the River and Plains Society Museums. This community collection of photography belongs to the people of Fort Benton, and it will continue to grow through your generosity. If you have photographs of the towns, ranches, farms, rivers, and people, stop by our Overholser Center. If you can part with them, we will add them to the collection. If you can’t part with them, but are willing to share them with the community, we’ll scan them into our digital photographic archives. Meanwhile enjoy the exhibition this summer as you reminisce about our forefathers when you visit the Museum of the Northern Plains, the Montana State Agricultural Museum, and the Homestead Village.

When Abe Lincoln signed the original Homestead Act into law in 1862, he reportedly announced, “This will do something for the little fellow.” The Act allowed “the little fellow,” men and unmarried women, American citizens age 21 or over, to claim up to 160 acres of public land and make homes for themselves and their families. David Carpenter filed the first homestead entry in Montana by 1 August 1868 on a claim just north of Helena. The first woman to file a claim was Margaret Maccumber of the Gallatin on 8 September 1870. Five years were required to patent or receive title to the land in those early years.

It wasn’t until the early 1900s that homesteading in Montana dramatically began to increase. Hardy Webster Campbell developed dry land farming techniques and the Great Northern Railroad promoted homestead settlements in Montana. In 1909 Campbell pronounced, “I believe of a truth that this region [including Montana] . . . is destined to be the last and best grain garden in the world. Good farming can be done here even better than in the humid region, but the work must be understood and carefully applied.”

Congress passed an Enlarged Homestead Act in 1909 allowing 320-acre claims and more flexibility for homesteaders to work at other jobs part of each year away from the claim. In 1912 the “prove-up” period was lowered from five to three years. With extensive advertising and promotion the homestead land rush to Montana was under way. Among the homesteaders pouring into Chouteau County during this period were my Robison grandparents, who with the related Applegate and Withrow families came by rail from Missouri to the Square Butte Bench area.

Many homesteaders came, but far fewer stayed. The wet years of the mid-1910s turned to dry years toward the end of this first decade, and the term “free land, no guarantee” became all too true. Our farmers of today are largely descended from the hardy first generation of homesteaders, who held down their debt in bad times, tenaciously worked hard and acquired more land in good times. We hope you enjoy our sampling of the images of these pioneer homesteaders as they arrived by Great Northern train, located their claims, built their claim shacks, established schools for their children, and carried out their daily work in the fields and in the homes.

Through the generosity of the McCardle family, you will see a model homestead, based on the A. J. McCardle homestead located near Flogan Coulee in the Hawarden area east of Geraldine. Built by son Leon McCardle, the model shows the 1912 sod claim shack build by his father. The other buildings are also built of sod, and the model provides an excellent example of an original homestead in Chouteau County.

Although many photographers took the photos in our collection of homesteading photography, two of them left an exceptional record of the own homesteading experience. Willard E. Barrows was an exceptional and prolific photographer. Barrows came from Nez Perce, Idaho, filing a homestead in the Pleasant Valley Community, February 7, 1910. Barrows lived and recorded nearly every aspect of the homestead period from 1910 to 1920. His interest in photography continued until the late 1940s. (Willard E. Barrows 1873-1951)

Using 4 by 5 inch dry-plate glass negative photography, Alexander DuBois recorded his adventures in Montana from 1914 to 1920. Alex came from the Midwest where he had taught high school and acquired the name “Professor.” Whether he was cutting timber and making ties for the Great Northern at Belton, visiting and recording the life of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph A. Baker at their Upper Highwood ranch, or working on his own homestead near Teton Ridge, Alex DuBois captured the action in a remarkable series of photographs. Alex and his wife Alma left their homestead and Montana by 1920, and moved to the Midwest where Alex worked as an electrical engineer in Chicago and Minnesota. (Alexander DuBois 1866-1966)

Among the photographs on display are several by Willard Barrows showing the arrival of the family in an emigrant car, loading their belongings on to wagons, moving on to the claim, breaking sod with a Case Steam Engine, a four-horse team pulling a bottom walking plow, three horses and two boys on a walking plow, celebrating Thanksgiving in 1912 inside the claim shack, building a sod claim shack, the LaBarre country school and the first Pleasant Valley school, wash day on the prairie using some clever “pedal power” techniques, children playing around the claim shack.

Photographs by Alexander DuBois show him building his claim shack, tents and claim shacks in winter, hauling and stacking hay, breaking sod and plowing with an eight horse team, a binder and team of horses cutting oats, stacked wheat in the fields, and a threshing outfit on the move complete with a cook house and milk cow.

Animals were important on the homestead. DuBois took many animal photographs including one striking photo of his wife Alma holding a young coyote pup in her arms inside the claim shack. Children are shown playing with toys inside and outside the house.

The chance for free land and opportunity proved irresistible to many. But homesteading was not a free lunch. It involved hardships that are difficult to imagine today. Setting off into an unknown, undeveloped area that to many appeared as a barren and harsh landscape was but the first of many challenges to face them. Some hoped for a second chance and a better life in an occupation for which they were ill prepared. Some were lured by the railroads with advertising for “a land of milk and honey.” Over time about 25% survived and succeeded in their homesteading experience. The other 75% failed, lost their land, and moved on. Those that persevered and prevailed paved the way for future generations. Descendants of these hearty homesteaders today live on the farms and ranches of Chouteau County.

(Sources: Montana’ Homestead Era by Daniel N. Vichorek; Homestead Days by T. Eugene Barrows)

Photos:

(1) A Threshing Outfit on the Move. Photo by Alex DuBois [Overholser Historical Research Center]

(2) Sohn’s Binder & Team Cutting Oats. Photo by Alex DuBois [Overholser Historical Research Center]

(3) Young Coyote in Arms of Mrs. Alma DuBois. Photo by Alex DuBois [Overholser Historical Research Center]

[Published in the Fort Benton River Press 11 July 2007. The article accompanied a Homestead Photography Exhibition at the entrance to the Museum of the Northern Great Plains during summer of 2007. This Exhibition will be in the Great Falls Public Library during May-June 2008.]

This continues the series of sketches by historians at the Joel F. Overholser Historical Research Center in Fort Benton.

The men and women who came to claim free land in Montana through homesteading faced many trials and tribulations as they worked through the good and bad times. Visual insight into the experiences of these hearty men, women, and children will be on display throughout this summer at the entrance to our Museum of the Northern Plains. The exhibition is built from the broad collection of imagery and memorabilia held at the Overholser Historical Research Center and the River and Plains Society Museums. This community collection of photography belongs to the people of Fort Benton, and it will continue to grow through your generosity. If you have photographs of the towns, ranches, farms, rivers, and people, stop by our Overholser Center. If you can part with them, we will add them to the collection. If you can’t part with them, but are willing to share them with the community, we’ll scan them into our digital photographic archives. Meanwhile enjoy the exhibition this summer as you reminisce about our forefathers when you visit the Museum of the Northern Plains, the Montana State Agricultural Museum, and the Homestead Village.

When Abe Lincoln signed the original Homestead Act into law in 1862, he reportedly announced, “This will do something for the little fellow.” The Act allowed “the little fellow,” men and unmarried women, American citizens age 21 or over, to claim up to 160 acres of public land and make homes for themselves and their families. David Carpenter filed the first homestead entry in Montana by 1 August 1868 on a claim just north of Helena. The first woman to file a claim was Margaret Maccumber of the Gallatin on 8 September 1870. Five years were required to patent or receive title to the land in those early years.

It wasn’t until the early 1900s that homesteading in Montana dramatically began to increase. Hardy Webster Campbell developed dry land farming techniques and the Great Northern Railroad promoted homestead settlements in Montana. In 1909 Campbell pronounced, “I believe of a truth that this region [including Montana] . . . is destined to be the last and best grain garden in the world. Good farming can be done here even better than in the humid region, but the work must be understood and carefully applied.”

Congress passed an Enlarged Homestead Act in 1909 allowing 320-acre claims and more flexibility for homesteaders to work at other jobs part of each year away from the claim. In 1912 the “prove-up” period was lowered from five to three years. With extensive advertising and promotion the homestead land rush to Montana was under way. Among the homesteaders pouring into Chouteau County during this period were my Robison grandparents, who with the related Applegate and Withrow families came by rail from Missouri to the Square Butte Bench area.

Many homesteaders came, but far fewer stayed. The wet years of the mid-1910s turned to dry years toward the end of this first decade, and the term “free land, no guarantee” became all too true. Our farmers of today are largely descended from the hardy first generation of homesteaders, who held down their debt in bad times, tenaciously worked hard and acquired more land in good times. We hope you enjoy our sampling of the images of these pioneer homesteaders as they arrived by Great Northern train, located their claims, built their claim shacks, established schools for their children, and carried out their daily work in the fields and in the homes.

Through the generosity of the McCardle family, you will see a model homestead, based on the A. J. McCardle homestead located near Flogan Coulee in the Hawarden area east of Geraldine. Built by son Leon McCardle, the model shows the 1912 sod claim shack build by his father. The other buildings are also built of sod, and the model provides an excellent example of an original homestead in Chouteau County.

Although many photographers took the photos in our collection of homesteading photography, two of them left an exceptional record of the own homesteading experience. Willard E. Barrows was an exceptional and prolific photographer. Barrows came from Nez Perce, Idaho, filing a homestead in the Pleasant Valley Community, February 7, 1910. Barrows lived and recorded nearly every aspect of the homestead period from 1910 to 1920. His interest in photography continued until the late 1940s. (Willard E. Barrows 1873-1951)

Using 4 by 5 inch dry-plate glass negative photography, Alexander DuBois recorded his adventures in Montana from 1914 to 1920. Alex came from the Midwest where he had taught high school and acquired the name “Professor.” Whether he was cutting timber and making ties for the Great Northern at Belton, visiting and recording the life of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph A. Baker at their Upper Highwood ranch, or working on his own homestead near Teton Ridge, Alex DuBois captured the action in a remarkable series of photographs. Alex and his wife Alma left their homestead and Montana by 1920, and moved to the Midwest where Alex worked as an electrical engineer in Chicago and Minnesota. (Alexander DuBois 1866-1966)

Among the photographs on display are several by Willard Barrows showing the arrival of the family in an emigrant car, loading their belongings on to wagons, moving on to the claim, breaking sod with a Case Steam Engine, a four-horse team pulling a bottom walking plow, three horses and two boys on a walking plow, celebrating Thanksgiving in 1912 inside the claim shack, building a sod claim shack, the LaBarre country school and the first Pleasant Valley school, wash day on the prairie using some clever “pedal power” techniques, children playing around the claim shack.

Photographs by Alexander DuBois show him building his claim shack, tents and claim shacks in winter, hauling and stacking hay, breaking sod and plowing with an eight horse team, a binder and team of horses cutting oats, stacked wheat in the fields, and a threshing outfit on the move complete with a cook house and milk cow.

Animals were important on the homestead. DuBois took many animal photographs including one striking photo of his wife Alma holding a young coyote pup in her arms inside the claim shack. Children are shown playing with toys inside and outside the house.

The chance for free land and opportunity proved irresistible to many. But homesteading was not a free lunch. It involved hardships that are difficult to imagine today. Setting off into an unknown, undeveloped area that to many appeared as a barren and harsh landscape was but the first of many challenges to face them. Some hoped for a second chance and a better life in an occupation for which they were ill prepared. Some were lured by the railroads with advertising for “a land of milk and honey.” Over time about 25% survived and succeeded in their homesteading experience. The other 75% failed, lost their land, and moved on. Those that persevered and prevailed paved the way for future generations. Descendants of these hearty homesteaders today live on the farms and ranches of Chouteau County.

(Sources: Montana’ Homestead Era by Daniel N. Vichorek; Homestead Days by T. Eugene Barrows)

Photos:

(1) A Threshing Outfit on the Move. Photo by Alex DuBois [Overholser Historical Research Center]

(2) Sohn’s Binder & Team Cutting Oats. Photo by Alex DuBois [Overholser Historical Research Center]

(3) Young Coyote in Arms of Mrs. Alma DuBois. Photo by Alex DuBois [Overholser Historical Research Center]

15 January 2007

“Like a wall of fire through a cane break”: The 1903 Fort Shaw Indian School Girls’ Basketball Team Sweeps Through Northern Montana

By Ken Robison

[Published in the Fort Benton River Press 17 January 2007]

This continues the series of historic sketches by historians at the Joel F. Overholser Historical Research Center in Fort Benton.

By the spring of 1903, the relatively new sport of basketball was sweeping through the state of Montana, and the girls’ basketball team from the Fort Shaw Indian School was emerging as an invincible force. During March of 1903, the Fort Shaw girls played the Agricultural College in Bozeman. In the words of the Great Falls Leader, Fort Shaw played their “most brilliant game,” defeating the older college girls 18-0 and scoring the first shut-out in Montana basketball history. The Leader sports editor gushed on to say that the Fort Shaw team “is walking through the state like a wall of fire through a cane break.” The Fort Shaw girls barnstormed this tour with convincing wins over Butte Parochial (modern day Butte Central), Bozeman, Boulder, and the university girls in Missoula.

Most spectators in Montana never before had watched a basketball game. A Great Falls Leader sports writer described the action in Luther’s Hall in the first basketball game ever played in the Electric City:

“Talk about excitement! Two wrestling matches, a football slaughter, three ping-pong tournaments, a ladies’ whist contest, a pink tea, and one Schubert musical recital combined, would fall short in comparison with one game of basket-ball as it is played. It was the first game ever seen in Great Falls, but there will be others. Five hundred and forty people paid cash at the box office for admission last night, besides those who had purchased tickets previously, so that in all there were over seven hundred people present, and the hall was packed like a sardine box, over 300 people standing about the end and sides of the wall. It was a success from a box office standpoint, and the shouting and enthusiasm would indicate that it also was a success from the audience point of view.

“Basket-ball is a game where you can be comfortable, carry the colors of your team, yell as loud and as long as you desire, wear your best bib and tucker, and witness a howling football match with the slaughter house elements cut out, while at the same time keeping your clothes and conscience as clean as the driven snow. The game is easy. To see it is to understand all about it, and this makes it a game above all others for the ladies. At each end of the hall there are hung about ten feet above the floor, what are termed baskets, but which are really dip nets, with an iron ring eighteen inches in diameter forming the top. The idea of each team is to get the round fat ten-inch football into their dip net, and when they do so it counts two--sometimes it counts one--but the referee obliging stops and tell what is, so there is no darkness upon this point.

“Between the baskets, or dip nets, there are a number of pretty figures traced upon the floor with chalk which forms the court, the outer boundaries being the first row of very excited spectators. The players are not supposed to play outside of the boundaries. Five girls on each side constitute a team, and two twenty-minute halves constitute the game. Last night there were three twelve-minute thirds, but that was entirely unaccording to Hoyle. The referee throws the ball up and then there is a mix, which makes the audience howl. A little bloomer girl shoots out of the pile and another little bloomer girl with short skirt over the bloomer part, hops on the first little girl, and the referee blows the whistle and separates the bunch. Then it all begins over again and half a dozen little girls slide head-first into the crowd after the fat ball and upset a few spectators in the slide. The referee blows his whistle and a very red-faced little bloomer lady with very much rumpled hair and both arms clasped tightly over the fat ball, emerges in triumph from the midst of chaos, and the crowd yells in ecstasy.

“More sliding, running, tumbling and mix-up; a little girl fires the fat ball for her fishnet and as it misses dropping in, the crowd groans ‘A-a-a-ah!’ in a tone which would indicate that the fishnet has been guilty of a personal affront. There are more mix-ups and half a dozen little girls manage to smash a chair, upset a fat man, break an electric light globe, and in the midst of it all a very excited little lady throws the fat ball toward the ceiling and it returns to fall safe in her fishnet, while the crowd yells like rooters, at Yale-Harvard finish. There is a rest between times and at the end the umpire announces the result and the audience comes out of a trance and declares the game to be the best ever.

“It might also be mentioned that the umpire is not killed in Basket-ball as in other ball games, and is a very pleasant faced young man armed with a time whistle and a package of chewing gum.

“For real fun and a chance to howl naturally, without appearing a rude, untamed person from Greater New York, basket-ball is the unadulterated essence of the proper thing and its initial appearance in Great Falls created a furor.”

Over a two-year period during 1902-03, Fort Shaw Superintendent F. C. Campbell built a traveling entertainment program far beyond simply the game of basketball. Drawing crowds of up to a thousand spectators, the Fort Shaw “show” typically consisted of music by a mandolin orchestra, demonstrations of Indian club swinging, literary recitations by scholars, followed by the main attraction, the basketball game. After the game, the host school often hosted a banquet or reception and dance for the Fort Shaw girls, completing the evening’s entertainment.

Despite the daunting travel schedules assembled by Superintendent Campbell, the girls met every challenge. Their opponents expected that the Fort Shaw team would arrive tired out from the travel and late hours, but the girls kept themselves in perfect condition. According to Campbell, “It might have been expected that they would be worn out, but they were too wise, and every game was played by the original members of the team, without substitution. Every afternoon, before a game, the girls took a bath and rub-down and then went to bed for a few hours and slept well. They would wake shortly before dinner, eat a light meal, have another rub-down and feel perfectly fresh when they went into a game.”

The Fort Shaw traveling road show drew huge crowds and rave notices in the press wherever they went. Campbell scheduled three types of contests for the girls. Against organized high school teams, Fort Shaw played a serious, conventional game of basketball. If the opponent had just organized a team, the Fort Shaw girls would provide a handicap, playing four of their girls against five or six opponents. If the host town had no team, the Fort Shaw girls would split their squad into two teams, giving an entertaining exhibition game of basketball.

In the absence of a girls’ basketball team at the high school in Great Falls, the Fort Shaw girls became “The Great Falls team,” receiving detailed press coverage by both the Tribune and the Leader.” To kick off a tour of northern Montana, Monday night, June 8th, the Fort Shaw team scheduled a game against the “first” Great Falls basketball team, the Grays, basically a club team since the Great Falls schools refused to organize a team. To even the match somewhat, the game was played under a handicap with the Great Falls team playing six girls, while the Fort Shaw team played only four girls.

The Great Falls Leader headlined the predictable result: “Was Absolutely Nothing To It. Four Little Indians Play Rings Around Six Home Girls. Just Like Shooting Fish. Nettie Wirth Makes Most Sensational Play Ever Recorded in Hall.” The Leader continued,

“There was a basketball game last evening at Luther’s hall between four little Indian girls of the Fort Shaw school and six little girls of the Great Falls teams. It was to have been a contest, but there was absolutely nothing to it and the four little Indian girls made rings about the home team at the final footing of 45 to 1, the worst score ever put up in the city.

“The game was intended to have been three little Indians against seven white girls, but Manager Hamill, of the home team felt that he would be taking too much advantage of the little Indians by allowing it to go that way and he made it six to four. It should have been seven to two. There were about 200 people present, and the little ladies all played with vim and dash, the only trouble with the home team being that they cannot play the game, while the Indians play like clockwork. It was one, two, three and a basket until the audience got tired of counting them and the Indians got tired of making them.

“The only count secured by the home team was on a free throw by Miss Pontet, saving a shut out. The sensational play of the evening, and the greatest ever seen in the halls was made by Nettie Wirth on a throw up of the ball, she reaching up and striking it square into the basket from the umpire’s hands, while her opponent gasped in astonishment.”

The Tribune added, “That the Great Falls Grays need coaching, and a great amount of it, is evident from the game which the girls of that team played with the Fort Shaw Indian maidens last night in this city . . . . Basketball is a splendid game, and one which brings rosy cheeks to the players, but to play the game as it should be played requires team work; and that is something which the local Grays lack to an alarming extent.”

The team lineups included the following girls:

Fort Shaw--Nettie Wirth, center; Genie Butch, right guard; Belle Johnson, left guard, and Emma Sansavere, forward. Left out was usual starting right guard, Josephine Langley.

Great Falls Grays--Edna Payne, center; Nellie Short, right forward; Flossie Solomon, left forward; Mamie Beckman, right guard; Mamie Longway, left guard, and Frances Pontet, substitute.

After a night at the Grand Hotel, the next morning, Tuesday the 9th of June, the Fort Shaw traveling road show consisting of orchestra, club swingers, scholars, basketball players, and chaperons, Superintendent Campbell, W. J. Peters and Miss Sadie F. Malley, boarded the Great Northern train to barnstorm through six towns in Northern Montana in six days. Two Fort Shaw basketball teams, called the “blues” and the “browns,” were scheduled to play a demanding series of exhibition games as follows:

June 9, Fort Benton.

June 10, Havre.

June 11, Chinook.

June 12, Harlem.

June 13 Glasgow.

June 14, Fort Peck, located at Poplar agency.

Tuesday evening Green’s Opera House in Fort Benton was the scene for the first exhibition game. The Fort Benton River Press reported, “The entertainment given last night at Green’s hall, which consisted of club swinging and basket ball by the Indian girls of the Fort Shaw Indian Industrial school, was a grand success, socially and financially. While both teams, the ‘blues’ and ‘browns’ acquitted themselves admirably in the games played by them, it was noticeable that the Misses Emma Sansavere, formerly a resident of Fort Benton, and Belle Johnson, a former resident of Highwood, were the favorites of the audience.”

Emma Sansavere, part Cree and the smallest member of the team, was born near Fort Assiniboine. Her mother, Mary Sansavere, was murdered about 1898 near Havre. Despite a concerted investigation by Chouteau County Attorney Charles N. Pray, no one was ever convicted for Mary’s murder. Belle Johnson, a part Piegan Blackfeet, was the daughter of early day miner, Charles Johnson, who came to Fort Benton by steamboat. Belle was born and raised near Belt and attended the Holy Family mission school on the Blackfeet reservation. Both Emma and Belle were exceptional athletes and basketball players.

The next day, the traveling show moved on to Havre. In the words of the Havre Plaindealer, “In every way a creditable entertainment was that given by the Fort Shaw Indian girls basket ball team at Swanton’s hall, Wednesday night. A match game between two teams was played before a large audience, many of whom had never seen a basket ball game, and but few had ever seen the Indian girls exemplify the sport. The Fort Shaw team enjoys the distinction of being the state champions, having defeated all the teams of the state. Briefly stated, the girls play a clever, fast and snappy game. The entertainment was fully enjoyed and was concluded by a dance following the game. Superintendent F. C. Campbell spoke briefly of the benefits of Indian education and of the progress made with the Indians who have come under Uncle Sam’s educational wing in this section of the state.”

Moving on to Chinook on Thursday evening, the Fort Shaw girls “gave an excellent exhibition of the game at the town hall . . . a very good and appreciative audience filled the hall.” After the exhibition was over the hosts held a social dance that continued until the early hours of Friday.”

Another day, another stop along the hi-line, this time at Harlem, where the Harlem Hearsay reporter in the Chinook Opinion reported, “The people of Harlem and vicinity were given a very pleasant and enjoyable time on Friday evening of last week, when the Fort Shaw Indian girls gave an entertainment consisting of a basket ball game and an exhibition of Indian club swinging. The game was a very good exhibition of team work and heady individual playing. In the first half the team work was somewhat broken on account of a substitute having to take the place of one of the regular players on the first team. The score at the end of the first half was 8 to 6 in favor of the first team. In the second half the substitute was taken off the first team and the remaining four regular players played the five on the second team. This was a big handicap, as it left one member of the second team free to play without any guard for interference, but the four played so much better team work, that the score at the end of the game was 25 to 10 in favor of the first team . . . . After the game several stayed to enjoy a social dance.”

On Saturday at Glasgow, the game proved so popular that the teams were asked to play again, so the girls played a second game on their return trip. At Poplar, the agency for the Fort Peck reservation, two games were played with admission charged at the first, while the second performance was free of charge to Indian children and the elderly.

Upon the return of the teams and chaperons to Great Falls on June 18th, Superintendent Campbell reported “The greatest interest in the game was shown at every place where we played, and I am satisfied that a team will be organized by the girls of each of the towns. We had a very pleasant trip, being able to travel in the daytime all the way, and the girls greatly enjoyed their visit, but are eager to get back to the school.” Campbell added, “The only unpleasant feature at any of those towns was the small size of the halls, it being impossible to accommodate all who desired to witness the games.”

The girls of Fort Shaw continued to play an exceptional brand of basketball. These remarkable young ladies were ambassadors for Indian education and trailblazers for their broad and popular acceptance as social and athletic equals. The next year, in the summer of 1904, “Montana’s team” barnstormed their way from Montana to St. Louis, Missouri. There at the St. Louis World’s Fair, the Fort Shaw Indian School Girls’ Basketball team gained immortality when they were crowned “1904 World Champions.”

[Sources: GFLD 16 Jan 1903, p. 4; GFTD 30 Jan 1903, p. 8; GFLD 2 Apr 1903, p. 6; GFTD 3 Jun 1903, p. 4; GFLD 9 Jun 1903, p. 7; GFTD 9 Jun 1903, p. 4; GFTD 11 Jun 1903, p. 3; GFTD 14 Jun 1903, p. 10; FBRPW 17 Jun 1903, p. 6; GFTD 19 Jun 1903, p. 3; FBRPW 17 Jun 1903, p. 6; Havre Plaindealer Weekly 13 Jun 1903, p. 1, 4; HPD 20 Jun 1903, p. 5; Chinook Opinion 18 Jun 1903, p. 5, 8]

Photos:

(1) The Fort Shaw Indian School Girls’ Basketball Team in 1903 [Great Falls Leader Photo 5 Feb 1904]

(2) How Basketball Is Played [Great Falls Leader Photo]

(3) Luther’s Hall in Great Falls, the “Home Court” for the Fort Shaw Indian School Girls’ Basketball Team. [Great Falls Leader Photo 19 Oct 1902]

(4) Green’s Opera House was located on the second floor of the Masonic Temple built in Fort Benton in 1880. Today, this historic building is the home of The Benton Pharmacy [Overholser Historical Research Center photo]

(5) Going To St. Louis for the 1904 World’s Fair [Great Falls Leader Photo 4 May 1904]

[Published in the Fort Benton River Press 17 January 2007]

This continues the series of historic sketches by historians at the Joel F. Overholser Historical Research Center in Fort Benton.

By the spring of 1903, the relatively new sport of basketball was sweeping through the state of Montana, and the girls’ basketball team from the Fort Shaw Indian School was emerging as an invincible force. During March of 1903, the Fort Shaw girls played the Agricultural College in Bozeman. In the words of the Great Falls Leader, Fort Shaw played their “most brilliant game,” defeating the older college girls 18-0 and scoring the first shut-out in Montana basketball history. The Leader sports editor gushed on to say that the Fort Shaw team “is walking through the state like a wall of fire through a cane break.” The Fort Shaw girls barnstormed this tour with convincing wins over Butte Parochial (modern day Butte Central), Bozeman, Boulder, and the university girls in Missoula.

Most spectators in Montana never before had watched a basketball game. A Great Falls Leader sports writer described the action in Luther’s Hall in the first basketball game ever played in the Electric City:

“Talk about excitement! Two wrestling matches, a football slaughter, three ping-pong tournaments, a ladies’ whist contest, a pink tea, and one Schubert musical recital combined, would fall short in comparison with one game of basket-ball as it is played. It was the first game ever seen in Great Falls, but there will be others. Five hundred and forty people paid cash at the box office for admission last night, besides those who had purchased tickets previously, so that in all there were over seven hundred people present, and the hall was packed like a sardine box, over 300 people standing about the end and sides of the wall. It was a success from a box office standpoint, and the shouting and enthusiasm would indicate that it also was a success from the audience point of view.

“Basket-ball is a game where you can be comfortable, carry the colors of your team, yell as loud and as long as you desire, wear your best bib and tucker, and witness a howling football match with the slaughter house elements cut out, while at the same time keeping your clothes and conscience as clean as the driven snow. The game is easy. To see it is to understand all about it, and this makes it a game above all others for the ladies. At each end of the hall there are hung about ten feet above the floor, what are termed baskets, but which are really dip nets, with an iron ring eighteen inches in diameter forming the top. The idea of each team is to get the round fat ten-inch football into their dip net, and when they do so it counts two--sometimes it counts one--but the referee obliging stops and tell what is, so there is no darkness upon this point.

“Between the baskets, or dip nets, there are a number of pretty figures traced upon the floor with chalk which forms the court, the outer boundaries being the first row of very excited spectators. The players are not supposed to play outside of the boundaries. Five girls on each side constitute a team, and two twenty-minute halves constitute the game. Last night there were three twelve-minute thirds, but that was entirely unaccording to Hoyle. The referee throws the ball up and then there is a mix, which makes the audience howl. A little bloomer girl shoots out of the pile and another little bloomer girl with short skirt over the bloomer part, hops on the first little girl, and the referee blows the whistle and separates the bunch. Then it all begins over again and half a dozen little girls slide head-first into the crowd after the fat ball and upset a few spectators in the slide. The referee blows his whistle and a very red-faced little bloomer lady with very much rumpled hair and both arms clasped tightly over the fat ball, emerges in triumph from the midst of chaos, and the crowd yells in ecstasy.

“More sliding, running, tumbling and mix-up; a little girl fires the fat ball for her fishnet and as it misses dropping in, the crowd groans ‘A-a-a-ah!’ in a tone which would indicate that the fishnet has been guilty of a personal affront. There are more mix-ups and half a dozen little girls manage to smash a chair, upset a fat man, break an electric light globe, and in the midst of it all a very excited little lady throws the fat ball toward the ceiling and it returns to fall safe in her fishnet, while the crowd yells like rooters, at Yale-Harvard finish. There is a rest between times and at the end the umpire announces the result and the audience comes out of a trance and declares the game to be the best ever.

“It might also be mentioned that the umpire is not killed in Basket-ball as in other ball games, and is a very pleasant faced young man armed with a time whistle and a package of chewing gum.

“For real fun and a chance to howl naturally, without appearing a rude, untamed person from Greater New York, basket-ball is the unadulterated essence of the proper thing and its initial appearance in Great Falls created a furor.”

Over a two-year period during 1902-03, Fort Shaw Superintendent F. C. Campbell built a traveling entertainment program far beyond simply the game of basketball. Drawing crowds of up to a thousand spectators, the Fort Shaw “show” typically consisted of music by a mandolin orchestra, demonstrations of Indian club swinging, literary recitations by scholars, followed by the main attraction, the basketball game. After the game, the host school often hosted a banquet or reception and dance for the Fort Shaw girls, completing the evening’s entertainment.

Despite the daunting travel schedules assembled by Superintendent Campbell, the girls met every challenge. Their opponents expected that the Fort Shaw team would arrive tired out from the travel and late hours, but the girls kept themselves in perfect condition. According to Campbell, “It might have been expected that they would be worn out, but they were too wise, and every game was played by the original members of the team, without substitution. Every afternoon, before a game, the girls took a bath and rub-down and then went to bed for a few hours and slept well. They would wake shortly before dinner, eat a light meal, have another rub-down and feel perfectly fresh when they went into a game.”

The Fort Shaw traveling road show drew huge crowds and rave notices in the press wherever they went. Campbell scheduled three types of contests for the girls. Against organized high school teams, Fort Shaw played a serious, conventional game of basketball. If the opponent had just organized a team, the Fort Shaw girls would provide a handicap, playing four of their girls against five or six opponents. If the host town had no team, the Fort Shaw girls would split their squad into two teams, giving an entertaining exhibition game of basketball.

In the absence of a girls’ basketball team at the high school in Great Falls, the Fort Shaw girls became “The Great Falls team,” receiving detailed press coverage by both the Tribune and the Leader.” To kick off a tour of northern Montana, Monday night, June 8th, the Fort Shaw team scheduled a game against the “first” Great Falls basketball team, the Grays, basically a club team since the Great Falls schools refused to organize a team. To even the match somewhat, the game was played under a handicap with the Great Falls team playing six girls, while the Fort Shaw team played only four girls.

The Great Falls Leader headlined the predictable result: “Was Absolutely Nothing To It. Four Little Indians Play Rings Around Six Home Girls. Just Like Shooting Fish. Nettie Wirth Makes Most Sensational Play Ever Recorded in Hall.” The Leader continued,

“There was a basketball game last evening at Luther’s hall between four little Indian girls of the Fort Shaw school and six little girls of the Great Falls teams. It was to have been a contest, but there was absolutely nothing to it and the four little Indian girls made rings about the home team at the final footing of 45 to 1, the worst score ever put up in the city.

“The game was intended to have been three little Indians against seven white girls, but Manager Hamill, of the home team felt that he would be taking too much advantage of the little Indians by allowing it to go that way and he made it six to four. It should have been seven to two. There were about 200 people present, and the little ladies all played with vim and dash, the only trouble with the home team being that they cannot play the game, while the Indians play like clockwork. It was one, two, three and a basket until the audience got tired of counting them and the Indians got tired of making them.

“The only count secured by the home team was on a free throw by Miss Pontet, saving a shut out. The sensational play of the evening, and the greatest ever seen in the halls was made by Nettie Wirth on a throw up of the ball, she reaching up and striking it square into the basket from the umpire’s hands, while her opponent gasped in astonishment.”

The Tribune added, “That the Great Falls Grays need coaching, and a great amount of it, is evident from the game which the girls of that team played with the Fort Shaw Indian maidens last night in this city . . . . Basketball is a splendid game, and one which brings rosy cheeks to the players, but to play the game as it should be played requires team work; and that is something which the local Grays lack to an alarming extent.”

The team lineups included the following girls:

Fort Shaw--Nettie Wirth, center; Genie Butch, right guard; Belle Johnson, left guard, and Emma Sansavere, forward. Left out was usual starting right guard, Josephine Langley.

Great Falls Grays--Edna Payne, center; Nellie Short, right forward; Flossie Solomon, left forward; Mamie Beckman, right guard; Mamie Longway, left guard, and Frances Pontet, substitute.

After a night at the Grand Hotel, the next morning, Tuesday the 9th of June, the Fort Shaw traveling road show consisting of orchestra, club swingers, scholars, basketball players, and chaperons, Superintendent Campbell, W. J. Peters and Miss Sadie F. Malley, boarded the Great Northern train to barnstorm through six towns in Northern Montana in six days. Two Fort Shaw basketball teams, called the “blues” and the “browns,” were scheduled to play a demanding series of exhibition games as follows:

June 9, Fort Benton.

June 10, Havre.

June 11, Chinook.

June 12, Harlem.

June 13 Glasgow.

June 14, Fort Peck, located at Poplar agency.

Tuesday evening Green’s Opera House in Fort Benton was the scene for the first exhibition game. The Fort Benton River Press reported, “The entertainment given last night at Green’s hall, which consisted of club swinging and basket ball by the Indian girls of the Fort Shaw Indian Industrial school, was a grand success, socially and financially. While both teams, the ‘blues’ and ‘browns’ acquitted themselves admirably in the games played by them, it was noticeable that the Misses Emma Sansavere, formerly a resident of Fort Benton, and Belle Johnson, a former resident of Highwood, were the favorites of the audience.”

Emma Sansavere, part Cree and the smallest member of the team, was born near Fort Assiniboine. Her mother, Mary Sansavere, was murdered about 1898 near Havre. Despite a concerted investigation by Chouteau County Attorney Charles N. Pray, no one was ever convicted for Mary’s murder. Belle Johnson, a part Piegan Blackfeet, was the daughter of early day miner, Charles Johnson, who came to Fort Benton by steamboat. Belle was born and raised near Belt and attended the Holy Family mission school on the Blackfeet reservation. Both Emma and Belle were exceptional athletes and basketball players.

The next day, the traveling show moved on to Havre. In the words of the Havre Plaindealer, “In every way a creditable entertainment was that given by the Fort Shaw Indian girls basket ball team at Swanton’s hall, Wednesday night. A match game between two teams was played before a large audience, many of whom had never seen a basket ball game, and but few had ever seen the Indian girls exemplify the sport. The Fort Shaw team enjoys the distinction of being the state champions, having defeated all the teams of the state. Briefly stated, the girls play a clever, fast and snappy game. The entertainment was fully enjoyed and was concluded by a dance following the game. Superintendent F. C. Campbell spoke briefly of the benefits of Indian education and of the progress made with the Indians who have come under Uncle Sam’s educational wing in this section of the state.”

Moving on to Chinook on Thursday evening, the Fort Shaw girls “gave an excellent exhibition of the game at the town hall . . . a very good and appreciative audience filled the hall.” After the exhibition was over the hosts held a social dance that continued until the early hours of Friday.”

Another day, another stop along the hi-line, this time at Harlem, where the Harlem Hearsay reporter in the Chinook Opinion reported, “The people of Harlem and vicinity were given a very pleasant and enjoyable time on Friday evening of last week, when the Fort Shaw Indian girls gave an entertainment consisting of a basket ball game and an exhibition of Indian club swinging. The game was a very good exhibition of team work and heady individual playing. In the first half the team work was somewhat broken on account of a substitute having to take the place of one of the regular players on the first team. The score at the end of the first half was 8 to 6 in favor of the first team. In the second half the substitute was taken off the first team and the remaining four regular players played the five on the second team. This was a big handicap, as it left one member of the second team free to play without any guard for interference, but the four played so much better team work, that the score at the end of the game was 25 to 10 in favor of the first team . . . . After the game several stayed to enjoy a social dance.”

On Saturday at Glasgow, the game proved so popular that the teams were asked to play again, so the girls played a second game on their return trip. At Poplar, the agency for the Fort Peck reservation, two games were played with admission charged at the first, while the second performance was free of charge to Indian children and the elderly.

Upon the return of the teams and chaperons to Great Falls on June 18th, Superintendent Campbell reported “The greatest interest in the game was shown at every place where we played, and I am satisfied that a team will be organized by the girls of each of the towns. We had a very pleasant trip, being able to travel in the daytime all the way, and the girls greatly enjoyed their visit, but are eager to get back to the school.” Campbell added, “The only unpleasant feature at any of those towns was the small size of the halls, it being impossible to accommodate all who desired to witness the games.”

The girls of Fort Shaw continued to play an exceptional brand of basketball. These remarkable young ladies were ambassadors for Indian education and trailblazers for their broad and popular acceptance as social and athletic equals. The next year, in the summer of 1904, “Montana’s team” barnstormed their way from Montana to St. Louis, Missouri. There at the St. Louis World’s Fair, the Fort Shaw Indian School Girls’ Basketball team gained immortality when they were crowned “1904 World Champions.”

[Sources: GFLD 16 Jan 1903, p. 4; GFTD 30 Jan 1903, p. 8; GFLD 2 Apr 1903, p. 6; GFTD 3 Jun 1903, p. 4; GFLD 9 Jun 1903, p. 7; GFTD 9 Jun 1903, p. 4; GFTD 11 Jun 1903, p. 3; GFTD 14 Jun 1903, p. 10; FBRPW 17 Jun 1903, p. 6; GFTD 19 Jun 1903, p. 3; FBRPW 17 Jun 1903, p. 6; Havre Plaindealer Weekly 13 Jun 1903, p. 1, 4; HPD 20 Jun 1903, p. 5; Chinook Opinion 18 Jun 1903, p. 5, 8]

Photos:

(1) The Fort Shaw Indian School Girls’ Basketball Team in 1903 [Great Falls Leader Photo 5 Feb 1904]

(2) How Basketball Is Played [Great Falls Leader Photo]

(3) Luther’s Hall in Great Falls, the “Home Court” for the Fort Shaw Indian School Girls’ Basketball Team. [Great Falls Leader Photo 19 Oct 1902]

(4) Green’s Opera House was located on the second floor of the Masonic Temple built in Fort Benton in 1880. Today, this historic building is the home of The Benton Pharmacy [Overholser Historical Research Center photo]

(5) Going To St. Louis for the 1904 World’s Fair [Great Falls Leader Photo 4 May 1904]

08 January 2007

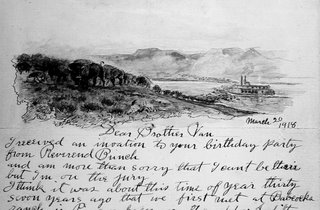

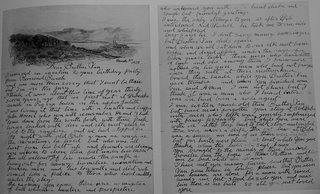

The Cowboy Artist and the Preacher: Charlie Russell Celebrates Brother Van’s Birthday in Fort Benton in 1918

By Ken Robison

[Published in the Fort Benton River Press 3 January 2007]

This continues the series of frontier sketches by historians at the Joel F. Overholser Historical Research Center in Fort Benton.

Fort Benton has had many friends over the years, but none finer than the famed cowboy artist, Charles M. Russell, and the beloved Methodist preacher Brother Van, Reverend William Wesley Van Orsdel.

Young Will Van Orsdel arrived at Fort Benton Sunday 30 June 1872 on the Coulson line steamboat Far West. That first day in Fort Benton Will preached the first sermon by a Protestant minister, and he acquired the name “Brother Van.”

Forty-six years later, on the evening of 22 March 1918, a large number of the friends of Bro. Van gathered at the Methodist Church in Fort Benton to celebrate the birthday anniversary of northern Montana’s famed pioneer preacher. The happy event was celebrated not only by the Fort Benton community but also by friends throughout Montana. In addition to expressions of respect and friendship delivered that night in person, telegrams and letters came in from around the state.